Oct 9, 2017

Chris Hedges

ANDERSON, Ind.—It was close to midnight, and I was sitting at a small campfire with Sybilla and Josh Medlin in back of an old warehouse in an impoverished section of the city. The Medlins paid $20,000 for the warehouse. It came with three lots. They use the lots for gardens. The produce they grow is shared with neighbors and the local homeless shelter. There are three people living in the warehouse, which the Medlins converted into living quarters. That number has been as high as 10.

“It was a house of hospitality,†said Josh, 33, who like his wife came out of the Catholic Worker Movement. “We were welcoming people who needed a place to stay, to help them get back on their feet. Or perhaps longer. That kind of didn’t work out as well as we had hoped. We weren’t really prepared to deal with some of the needs that people had. And perhaps not the skills. We were taken advantage of. We weren’t really helping them. We didn’t have the resources to help them.â€

“For the Catholic Workers, the ratio of community members to people they’re helping is a lot different than what we had here,†Sybilla, 27, said. “We were in for a shock. At the time there were just three community members. Sometimes we had four or five homeless guests here. It got kind of chaotic. Mostly mental illness. A lot of addiction, of course. We don’t know how to deal with hard drugs in our home. It got pretty crazy.â€

Two or three nights a month people gather, often around a fire, in back of the warehouse, known as Burdock House.

“The burdock is seen as a worthless, noxious weed,†Josh said. “But it has a lot of edible and medicinal value. A lot of the people we come into contact with are also not valued by our society. The burdock plant colonizes places that are abandoned. We are doing the same thing with our house.â€

Those who come for events bring food for a potluck dinner or chip in five dollars each. Bands play, poets read and there is an open mic. Here they affirm what we all must affirm—those talents, passions, feelings, thoughts and creativity that make us complete human beings. Here people are celebrated not for their jobs or status but for their contributions to others. And in associations like this one, unseen and unheralded, lies hope.

“We are an intentional community,†said Josh. “This means we are a group of people who have chosen to live together to repurpose an old building, to offer to a neighborhood and a city a place to express its creative gifts. This is an alternative model to a culture that focuses on accumulating as much money as possible and on an economic structure based on competition and taking advantage of others. We value manual labor. We value nonviolence as a tactic for resistance. We value simplicity. We believe people are not commodities. We share what we have. We are not about accumulating for ourselves. These values help us to become whole people.â€

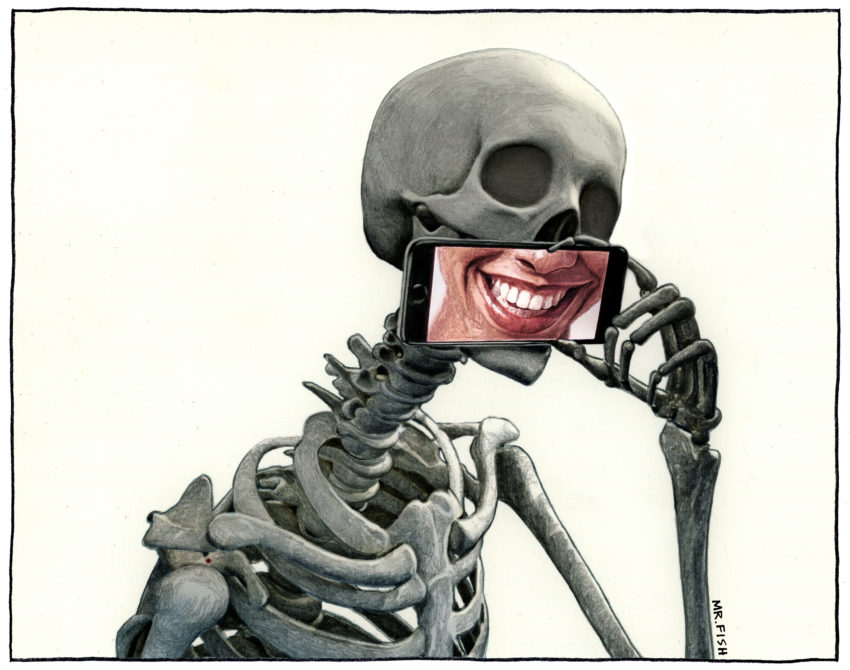

The message of the consumer society, pumped out over flat screen televisions, computers and smartphones, to those trapped at the bottom of society is loud and unrelenting: You are a failure. Popular culture celebrates those who wallow in power, wealth and self-obsession and perpetuates the lie that if you work hard and are clever you too can become a “success,†perhaps landing on “American Idol†or “Shark Tank.†You too can invent Facebook. You too can become a sports or Hollywood icon. You too can rise to be a titan. The vast disparity between the glittering world that people watch and the bleak world they inhabit creates a collective schizophrenia that manifests itself in our diseases of despair—suicides, addictions, mass shootings, hate crimes and depression. Our oppressors have skillfully acculturated us to blame ourselves for our oppression.

Hope means walking away from the illusion that you will be the next Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Kim Kardashian. It means rejecting the lust for public adulation and popular validation. It means turning away from the maniacal creation of a persona, an activity that defines presence on social media. It means searching for something else—a life of meaning, purpose and, ultimately, dignity.

The bottomless narcissism and hunger of consumer culture cause our darkest and most depraved pathologies. It is not by building pathetic, tiny monuments to ourselves that we become autonomous and free human beings; it is through acts of self-sacrifice, by recovering a sense of humility, by affirming the sanctity of others and thereby the sanctity of ourselves. Those who fight against the sicknesses, whether squatting in old warehouses, camped out at Zuccotti Park or Standing Rock or locked in prisons, have discovered that life is measured by infinitesimal and often unseen acts of solidarity and kindness. These acts of kindness, like the nearly invisible strands of a spider’s web, slowly spin outward to connect our atomized and alienated souls to the souls of others. The good, as Daniel Berrigan told me, draws to it the good. This belief—held although we may never see empirical proof—is profoundly transformative. But know this: When these acts are carried out on behalf of the oppressed and the demonized, when compassion defines the core of our lives, when we understand that justice is a manifestation of this solidarity, even love, we are marginalized and condemned by the authoritarian or totalitarian state.

Those who resist effectively will not negate the coming economic decline, the mounting political dysfunction, the collapse of empire, the ecological disasters from climate change, and the many other bitter struggles that lie ahead. Rather, they draw from their acts of kindness the strength and courage to endure. And it will be from their relationships—ones formed the way all genuine relationships form, face to face rather than electronically—that radical organizations will be created to resist.

Sybilla, whose father was an electrician and who is the oldest of six, did not go to college. Josh was temporarily suspended from Earlham College in Richmond, Ind., for throwing a pie at William Kristol as the right-wing commentator was speaking on campus in 2005. Josh never went back to college. Earlham, he said, like most colleges, is a place “where intellectualism takes precedence over truth.â€

“When I was in high school I was really into the punk rock community,†Sybilla said. “Through that I discovered anarchism.â€

“Emma Goldman?†I asked.

“Yeah, mostly that brand of anarchism,†she said. “Not like I’m going to break car windows for fun.â€

She was attracted to the communal aspect of anarchism. It fit with the values of her parents, who she said “are very anti-authoritarian†and “who always taught me to think for myself.†She read a book by an anonymous author who lived outside the capitalist system for a couple of years. “That really set me on that direction even though he is a lot more extreme,†she said, “only eating things from the garbage. Train hopping. As a teenager, I thought, ‘Wow! The adventure. All the possible ways you could live an alternative lifestyle that’s not harmful to others and isn’t boring.’ â€

When she was 18 she left Anderson and moved to Los Angeles to join the Catholic Worker Movement.

“I [too] became pretty immersed in the anarchist scene,†Josh said. “I’m also a Christian. The Catholic Worker Movement is the most well known example of how to put those ideas in practice. Also, I really didn’t want anything to do with money.â€

“A lot of my friends in high school, despite being a part of the punk rock community, went into the military,†Sybilla said. “Or they’re still doing exactly what they were doing in high school.â€

The couple live in the most depressed neighborhood of Anderson, one where squatters inhabit abandoned buildings, drug use is common, the crime rate is high, houses are neglected and weeds choke abandoned lots and yards. The police often never appear when someone from this part of the city dials 911. When the police do appear they are usually hostile.

“If you’re walking down the street and you see a cop car, it doesn’t make you feel safe,†Josh said.

“A lot of people view them [police] as serving the rich,†Sybilla said. “They’re not serving us.â€

“Poor people are a tool for the government to make money with small drug charges,†she added. “A lot of our peers are in jail or have been in jail for drugs. People are depressed. Lack of opportunity. Frustration with a job that’s boring. Also, no matter how hard you want to work, you just barely scrape by. One of our neighbors who is over here quite a bit, he had a 70-hour-a-week job. Constant overtime. And he still lives in this neighborhood in a really small one-bedroom apartment. I think Anderson has really bad self-esteem. A lot of young people, a lot of people my age I know are working for $9, $10 an hour. Moving from job to job every six months. Basically, enough money to buy alcohol, cigarettes and pay the rent.â€

“My mom’s generation grew up thinking they were going to have a solid job,†she said. “That they were just going to be able to start a job and have a good livelihood. And that’s not the case. Just because you want to work really hard it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to make it.â€

“I work as a cashier at the local Christian college,†she said. “It’s a small school with 2,000 students. I work in the cafeteria. The contract changed. The school stopped doing its own food service many years ago. Has been hiring private companies. After I worked there for a year the contract was up. It was a new company and they’re huge. … I think it’s the biggest food service company. They do most hospitals, schools, prisons. And the job conditions changed so dramatically. Our orientation with this new company, they had this HR guy come. He’s like, ‘You’re going to work for the biggest company in the world. You should be so excited to be a part of our team. We’re going to make you great. Anderson used to be this really powerful city full of industry. The employees demanded so much from the companies. And [the companies] all left.’ â€

“We’re just looking at him,†she said. “Why is this relevant? Basically the message was, ‘You guys have no other choice. So you don’t choose to work with us. You have to. And we’re going to do what we want you to do.’ At the time I was taking $7.50 an hour. They hired me at $7.50 from the old company. They hired the people beside me for $8, which I was not happy with. The old employees were making more money because they got consistent raises throughout the years. They would have them do jobs like carrying crates of heavy food up the stairs. Or they moved them to the dish room. Jobs that they knew they physically couldn’t do, in hopes that they would quit. I think. They didn’t want to pay that higher wage. And the students weren’t happy either. So many employees were really upset. Everyone was talking about quitting. We lost about half the workforce. There were 100 employees when they came in. They had reduced down to 50. That makes my job twice as hard. But I still make $7.50. With no hope for a raise anytime soon.â€

“I went up to them,†she continued. “I said, ‘I need to make as much as these people at least. I’ve been here for a year. I’m a more valuable employee.’ And they were like, ‘If you don’t like it, quit. Maybe you can get a job at Burger King.’ I was so angry. How dare they tell me to quit. I started talking to some of my co-workers to see if they were interested in making the job better rather than quitting. And a lot of them were. Especially the people who’d been there for years and years and who were familiar with GM and UAW [the United Automobile Workers union]. And weren’t scared of it. So we started having meetings. I think the campaign took two years. And we successfully organized. It’s been a huge improvement. Even though it’s still a low-paying job, everything is set. They can’t change their mind about when we get raises. They can’t change their mind about what the hiring rate is. They can’t take these elderly people and make them start carrying boxes rather than run a cash register. They were also firing people for no reason. That doesn’t happen anymore. … The employees have a voice now. If we don’t like something, when our contract is up for renegotiation we can change it.â€

“The jobs we have are boring,†she said. “My job was so boring. Having this as an outlet, also with the challenge of creating the union there, I was able to not feel so useless.â€

Sybilla also publishes The Heartland Underground. The zine, which sells for $2 a copy and comes out every four or five months, reviews local bands like the punk group Hell’s Orphans, publishes poets and writers and has articles on subjects such as dumpster diving.

In a review of Hell’s Orphans, which has written songs such as “Too Drunk to Fuck†and “Underage Donk,†the reviewer and the band sit in a basement drinking until one of the band members, Max, says, “Feel free to take anything we say out of context. Like, you can even just piece together individual words or phrases.†(Donk, as the article explains, is “a slang term for a very round, attractive, ghetto booty and is a derivative of the term Badonkadonk.â€) The review reads:

Hell’s Orphans has really played some unusual shows like a high school open house, a show in a garage where the audience was only four adults, four kids, a dog and a chicken, and out of the Game Exchange a buy/sell/trade video game store. They’ve also played under some uncomfortable circumstances like a flooded basement in which Nigel was getting shocked by the mic and guitar every few seconds and at the Hollywood Birdhouse one night when Max and Nigel were both so paranoid on some crazy pot that they were also too frozen to perform and couldn’t look at the audience. For such a young band that has done zero touring they’ve had a lot of adventures and experiences.

A poet who went by the name Timotheous Endeavor wrote in a poem titled “The Monkey Songâ€:

please just let me assume

that there is room for us and our lives

somewhere between your lies

and the red tape that confinesplease just let me assume

we’re all monkeys

we’re trained to self alienate

but it’s not our fatesi was walking down the road

i wonder if there’s anywhere around here

that i am truly welcome

spend my dollar move along

past all of the closed doors

In one edition of The Heartland Underground there was this untitled entry:

They pay me just to stay out of thier [sic] world. They don’t want me at work I would just get in their way. They pay me just to sit at home. I feel things harder and see with such different eyes it’s easier for everyone if I just stay at home, if I just stay out of their world and wait to die. I am not inept. I just don’t fit into their neatly paved grids, their machines and systems.

There is no place for a schizophrenic in this world and there is no place for anything wild, crooked, or untamed anymore. When did things go so wrong? Everything is wrong!! They paved paradise and put up a parking lot. They paved the entire fucking planet. I’m on a mission to liberate myself from all the lies that poison me and rot inside my mind, holding me captive and causing me to hate myself and the world. I’m ready to stop hating! I’m ready to become fully human and join life.

The truth is: We’re all drowning.

They think I’m crazy? At least I can see that I’m drowning. No one else is in a panic because they can’t see or feel how wrong everything is. I don’t want to drown. I want to swim and climb up to a high place. I want to rise above.

Arbitrary Aardvark wrote an article called “I was a Guinea Pig for Big Pharma,†about earning money by taking part in medical experiments. He would stay in a lab for about two weeks and take “medicine, usually a pill, and they take your blood a lot. You might be pissing in a jug or getting hooked up to an EKG machine or whatever the study design calls for, and they take your blood pressure and temperature pretty often.†He made between $2,000 and $5,000 depending on how long the study lasted. Most of his fellow “lab rats†were “just out of jail or rehab.†In one study he had a bullet-tipped plastic tube inserted down his nose into his intestines. “It was the most painful thing I’ve been through in my adult life.†He said he and the other subjects did not like reporting side effects because they were “worried that they’ll be sent home without a full paycheck, or banned from future studies.†He admitted this probably affected the viability of the studies. He became ill during one of the experiments. The pharmaceutical company refused to pay him, blaming his illness on a pre-existing condition. He wrote:

I signed up for one that was going to pay $5,000, but a week into it my liver enzymes were all wrong, and they took me out of the study but kept me at the site, because I was very sick. It turned out I’d come down with mono just before going into the study. And then I got shingles, not fun. …

I’d spent 3 years trying to be a lawyer and failed. I’d worked in a warehouse, as the Dalai lama’s nephew’s headwaiter, as a courier and a temp. Lost money day trading and then in real estate. I was ready to try medical experiments again. I tried 3 times to get in at Eli Lilly but never did. Lilly no longer does its own clinical trials after a girl … killed herself during an anti-depressant study. …

Jared Lynch wrote an essay titled “Sometimes the Voices in Your Head are Angry Ghosts†that included these lines:

Death shrouded the whole spacetime of the latter half of high school, coating it in an extra vicious layer of depression. The first night we stayed in the house I sat in the living room, writing about ghosts in a composition book… I had a package of single edge blades in the back of my top desk drawer and sometimes I flirted too closely with that edge of darkness. I thought a lot about the blades at school. My daydreams were consumed by untold suicides, and countless times I came home to find one of my past selves in the tub with his forearm opened wide and grinning with his life essence surrounding him in the tub on the wrong side of his skin.

It was a strange, beautiful time. Melancholia wrapped around the edges with the golden glow of nostalgia for a time that felt like I had died before it existed… I fell into an expected, but incredibly deep pool of depression and I found the single edge razors that one of my future had so graciously left behind in my top drawer. I bled myself because I wanted to be with the lovely, lonely ghosts. I bled myself more than I ever had, but I didn’t bleed enough to capture myself in the barbs of the whirlpool of my depression.

He ended the essay with “I still bear my scars.â€

Tyler Ambrose wrote a passage called “Factory Blues.â€

What is a factory? What is a factory? A factory is a building of varied size. Some immense tributes to humanistic insatiability, others homely, almost comfortable. Mom and Pop type places, each run-down corner lot a puzzle piece in a greater maze. Gears if you will, all part of the capitalism machine. Some so small they fall out like dandruff, plummeting into the furnaces that keep the monster thriving. Constantly shaking loose another drop of fuel from its decaying hide. For the more fuel it consumes, the drier and deader does its skin become. Until one day, when all the skin has fallen into the fires, and all that remains are rustic factory bones, the beast will fall, and all the peoples of the earth will feel its tumble. And all will fall beside it, when its decaying stench kills the sun.

The cri de coeur of this lost generation, orphans of global capitalism, rises up from deindustrialized cities across the nation. These Americans struggle, cast aside by a society that refuses to honor their intelligence, creativity and passion, that cares nothing for their hopes and dreams, that sees them as cogs, menial wage slaves who will do the drudgery that plagues the working poor in postindustrial America.

Parker Pickett, 24, who works at Lowe’s, is a poet and a musician. He frequently reads his work at Burdock House. He read me a few of his poems. One was called “This is a poem with no Words.†These were the concluding lines.

out of, the affection I receive from concrete whether broken or spray

painted, the old men want that money now want that control even

though they are sad and delusional, if I could I would die from the beauty

of her eyes as they shudder and gasp and relax with natural imperfections which

I hold in high regards, the glow of the city around me reaches to the night

sky, a slate of black chalkboard I wipe off the stars with my thumb one

by one, songs end stories end lives end, but the idea of some grand, silly

truth to everyone and everything with never die, we are born in love with precious life, and with that truth I will giggle and smile until I’m laid to rest in my

sweet, sweet grave.

I sat on a picnic table next to Justin Benjamin. He cradled his guitar, one of his tuning pegs held in place by locking pliers. The fire was dying down. Justin, 22, calls himself WD Benjamin, the “WD†being short for “well dressed.†He wore a white shirt, a loosely knotted tie and a suit coat. He had long, frizzy hair parted in the middle that fell into his face. His father was a steelworker. His mother ran a day care center and later was an insurance agent.

“Kids would talk about wanting something better or leaving,†he said. “Yet they weren’t doing steps to take it. You saw they were going to spend their whole lives here begrudgingly. They would talk stuff. They would never do anything about it. It was all just talk.â€

He paused.

“Substance [abuse] ruined a lot of lives around here,†he said.

He estimates that by age 14 most kids in Anderson realize they are trapped.

“We had seen our parents or other people or other families not go anywhere,†he said. “This business went under. Pizzerias, paint stores, they all go under. About that time in my life, as much as I was enthralled with seeing cars rushing past and all these tall buildings, we all saw, well, what was the point if none of us are happy or our parents are always worrying about something. Just not seeing any kind of progression. There had to be something more.â€

“I’ve had friends die,†he said. “I had a friend named Josh. We’d say, ‘He Whitney Houston-ed before Whitney Houston.’ He pilled out and died in a bathtub. It happened a month before Whitney Houston died. So that was a weird thing for me. Everyone is going to remember Whitney Houston but no one will remember Josh. At the time he was 16.â€

“I see friends who are taking very minimal jobs and never thinking anywhere beyond that,†he said. “I know they’re going to be there forever. I don’t despise them or hold anything against them. I understand. You have to make your cut to dig out some kind of a living. … I’ve done manual labor. I’ve done medical, partial. Food service. I’ve done sales. Currently I’m working on a small album. Other than that, I play for money. I sell a lot of odds and ends. I’ve been doing that for years. Apparently I have a knack for collecting things and they’re of use for somebody. Just paying my way with food and entertainment for somebody. I live right across from the library. Eleventh Street. I can’t remember the address. I’m staying with some people. I try to bring them something nice, or make dinner, or play songs. I do make enough to pay my share of utilities. I wouldn’t feel right otherwise.â€

He is saved, he said, by the blues—Son House, Robert Johnson, all the old greats.

“My finger got caught in a Coke bottle trying to emulate his style of slide guitar,†he said of House. “I asked my dad to help me please get it out. There was just something about people being downtrodden their whole lives. I used to not understand the plight of the black community. I used to think why can’t they just work harder. I was raised by a father who was very adamant about capitalism. Then one day my sister-in-law told me, ‘Well, Justin, you just don’t understand generational poverty. Please understand.’ People were told they were free yet they have all these problems, all these worries. … It’s the natural voice. You listen to Lead Belly’s ‘Bourgeois Blues,’ it’s a way of expressing their culture. And their culture is sad. ‘Death Don’t Have No Mercy’ talks about the great equalizer of death. It didn’t matter if you’re black or white, death will come for you.â€

He bent over his guitar and played Robert Johnson’s “Me and the Devil Blues.â€

Early this morning

When you knocked upon my door

Early this morning, oooo

When you knocked upon my door

And I said hello Satan

I believe it’s time to go

“I’ve seen a lot of GM people, they just live in this despair,†he said of the thousands of people in the city who lost their jobs when the General Motors plants closed and moved to Mexico. “They’re still afraid. I don’t know what they’re afraid of. It’s just the generation they came out of. I worked with plenty of GM people who were older and having to work for their dollars begrudgingly. They’re like, ‘I was made promises.’ â€

“I was born 3 pounds,†he said. “I was not destined for this world. Somehow I came out. I did the best I could. That’s all I’ve done. I’ll never say I’m good at anything. At least I have the ability to think, speak and act. Three pounds to this now. I just can’t see the use of not fighting. You always have to think about what’s going to lay down in the future. What’s going to happen when the factories close down? Are you going to support your fellow co-workers? Are you going to say, ‘No, things will come back?’ Are you going to cast everything to damnation? Cast your neighbors down, say it was their fault the jobs are gone.â€

“I’ve never seen the heights of it,†he said of capitalism. “But I’ve seen the bottom. I’ve seen kids down here naked running around. I’ve seen parents turn on each other and kids have to suffer for that. Or neighbors. I’d just hear yelling all night. It’s matters of money. It’s always the kids that suffer. I always try to think from their perspective. When it comes down to kids, they feel defeated. When you grow up in a household where there’s nothing but violence and squabbling and grabbing at straws, then you’re going to grow up to be like that. You’re going to keep doing those minimum jobs. You’re fighting yourself. You’re fighting a system you can’t beat.â€

“I’ve seen poets, phenomenal guitarists, vocalists, percussionists, people who have tricks of the trade, jugglers, yo-yo players, jokesters,†he went on. “I admire those people. They might go on to get a different job. They might find a sweetheart. They might settle down. They have that thing that got them to some point where they could feel comfortable. They didn’t have to work the job that told them, ‘So what if you leave? You don’t matter.’ I know a fellow who works at the downtown courthouse. Smart as can be. One of my favorite people. We talk about Nietzsche and Kafka in a basement for hours. The guy never really let the world get him down. Even though he’s grown up in some rough situations.â€

And then he talked about his newborn niece.

“I wrote this in about 10 minutes,†he said. “I race down the street because no one else was available. I went to a friend. I said, ‘I wrote a song! I think it’s neat. I don’t think it’s good. But I like the idea.’ I’d never done that.â€

He hunched back over his guitar and began to play his “Newborn Ballad.â€

You were brushed and crafted carefully

They knew young love and now they know you

How two lives figure into one beats me

But either I’m sure they’ll agree with youYour eyes will open proud I pray

May the breakneck sides around you come down

Little darling I’ll be your laughing stock

So the mean old world won’t get you downI ain’t gonna say I ain’t crazy

All are fronting and pestering your soul

When we first meet I can promise to

To listen, to play with, to talk to, to loveThere’s nothing no better they’ll tell you

Than your youth, no weight will end

No matter the preference child hear me

Not a moment you’ll have will be absentMy pardon, my dearest apologies

For the scenes and the faces I make

For now you might find them quite funny

But they’ll get old as will I, I’m afraidYour comforts they don’t come easy

With an hour twenty down the road

We made lives in telling you sweetly

But you can make it, we love you, you know.

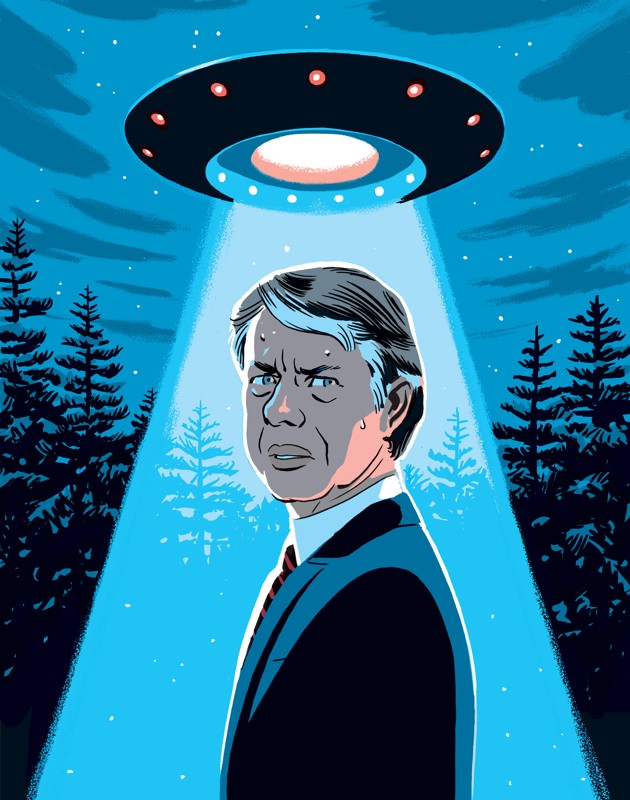

Mr. Fish

Mr. Fish